As discussed earlier this month in Uncovering the History of the Tiffany Girls, remarkable women helped Louis Comfort Tiffany realize his unique vision for the decorative arts, but the story of his jewelry designers, Julia Munson and Meta Overbeck, has yet to be fully told.

Louis’ enduring collaborations with women artists in various fields of the decorative arts—blown glass, bronze, stained glass windows, enamels, ceramics—indicate how remarkably progressive he was for his day. Not only did he seek them out as employees, but one of his first partners in the interior design business was Candace Wheeler, a textile artist. In the studio, he valued women’s “dexterity and skill” but they had another advantage he had identified—to quote Janet Zapata, former Tiffany archivist and pre-eminent scholar, color was “a lifetime obsession of Tiffany’s, evident throughout his career no matter what medium he chose for his creativity.” Apparently, Tiffany had observed what neuroscientists have since established, though the exact biological mechanism has yet to be discovered: women are markedly more adept at distinguishing among colors, and verbalizing these differences, than are men. Further, they appear to have a “markedly disparate” capability to categorize fine differences in the green-blue region, as well as yellow-orange—hues to which Tiffany was almost single-mindedly devoted.

When Louis Comfort Tiffany turned to the art of jewelry, he chose, as his first collaborator, Julia Munson, a recent art school graduate training in the enamels department. He had hired her in 1898 to help him with enamels, and she was assisting him and his team, Dr. Parker McIlhenny and Patricia Gay, to “work out formulas and designs.” This venture into jewelry was undertaken in “secrecy,” because, according to Zapata, Louis was “more than a little intimidated” by the internationally acclaimed jewels his father and Paulding Farnham had created. Julia was at first quietly installed in the studio on the top floor of his New York mansion, and later worked in the 23rd Street studio. Tiffany and Munson’s output, spanning the years between approximately 1902 and 1914, is among the most unusual and distinctive jewelry ever made. Louis Comfort Tiffany’s well-known statement, that his jewels were his “little missionaries of art” to revolutionize taste in the medium, relates in particular to the striking and experimental work of this first period.

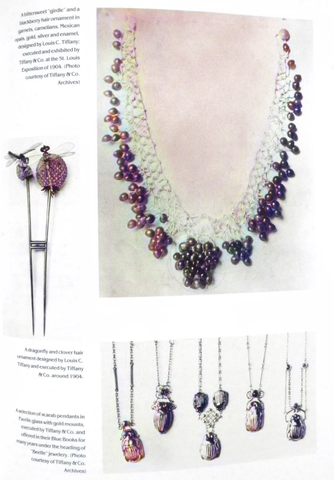

These early jewels, especially those created for the 1904 St. Louis Exposition, convey a touching fragility, reflecting the delicacy of the humble wayside plants and flowers that were Tiffany’s inspiration. The hand of the artist is intentionally made evident, and, as Tiffany directed, these evocative pieces have a palette characterized by “hues only nature could produce”—carefully engineered shades of enamels in the orange-yellow-green-blue range of the spectrum that had been achieved thanks to his staff’s thorough, orderly experiments with metallic oxides. Meant to reflect biological growth, the jewels are irregular in form, sometimes containing uneven apertures, their organic appearance enhanced by the way the gemstones were partially buried within their foliate mountings, as though they had originated there. The jewels from this period were three dimensionally conceived as fully realized works of art incorporating motifs on the front, sides and reverse with an organic unity.

Louis Comfort Tiffany and Julia Munson worked intensively for two years to achieve the quality he deemed necessary for his studio’s first exhibition, at the international St. Louis Exposition of 1904. Of the 27 pieces they submitted, only one appears to have survived, the black opal grapevine necklace at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—and even this is substantially altered. Black and white images accompanied by descriptions survive to help paint a picture of how extraordinary these jewels were; among them were an enamel clover blossom tiara with diamond dew drops, a dandelion flower hair ornament with enameled leaves and buds “tied together by a string,” and a blackberry spray brooch composed of carved garnets and carnelians in graduating shades chosen to reflect every stage in the maturation of blossom and berries. Tiffany and Munson achieved a new type of “realism” that went beyond what his father and Paulding Farnham had done; these were not mere simulations of ideal flowers, but jewels that fully captured the tenuous, delicate beauty of the organic world that changed from moment to moment, as though in a stop action photo. They also created historicist designs, which one particular critic remarked on the feeling and connection that their graceful Etruscan necklaces had to their actual ancient world counterparts, noting that their Etruscan necklaces were "beautiful enough to have been exhumed from a tomb of Chiusi or Volterra.” The grapevine motif that was so connected to their early success remained a leitmotif throughout their collaboration, and these elegant jewels show an unusual degree of design unity.

Judging by the work produced while she was head of the jewelry department, Julia Munson, like the men and women who brought Louis Comfort Tiffany’s designs in other media to fruition, was an unsung master of her art. At Tiffany Studios New York, and later at Tiffany & Co., Tiffany embraced the role of Renaissance studio master, and Munson addressed him, and spoke of him as “master,” her demeanor ever “careful and deferential.” One later journalist wrote that Julia had “an acute ability to translate the master’s large scale designs into the world of the minuscule.”

The amount that Louis Comfort Tiffany, Julia Munson, and colleagues taught themselves and accomplished in a studio setting is notably impressive. Although we don’t know how much Julia crafted herself—she is recorded as having “designed and made” a brooch commissioned by the millionaire Charles Schwab—she must have had some ability with not only enamel, but also metalsmithing. Within a few years, her staff of men and women were also able to execute challenging work in platinum group metals. Though some firms already had platinum expertise by this time, the metal group was notoriously difficult and relatively new, typically requiring an extended apprenticeship in an established workshop. Additionally, many jewels from the period of their collaboration integrate the technique of exquisitely delicate plique-à-jour enamel in subtle hues—again, a challenging skill to master. Munson expertly supervised and managed the large group of craftspeople dedicated to these arts, and Tiffany trusted and delegated to her. Though he was a strict and demanding taskmaster, intensely concerned with the success of the jewelry project during this period, he not only passed her his sketches of jewelry ideas to execute, but encouraged her to design her own work.

At the 1904 St. Louis exposition, their work was hailed by critics as a triumph, exceeding Tiffany’s expectations, and this brought perks for Munson. It is said she earned $10,000 per year at the peak of her career—approximately $200,000 today—a generous sum for the time, “especially for a woman.” According to a family source, Tiffany brought Munson with him on business travel to Europe. If this is true (only one transatlantic record from 1913 has been located), perhaps in earlier years, they had visited the Paris Salons where they exhibited and met with Tiffany’s agent there, Siegfried Bing. This is speculation, however, during this luminous and productive period of her life, she and Tiffany certainly embraced and explored a shared artistic purpose. One of Munson’s grandnieces recalled their later relationship as one of “respect and admiration”; she also suggested there may have been a romantic aspect to it, but this is unsubstantiated by any other source.

In 1914, Julia Munson’s career at Tiffany Studios New York abruptly ended when she married at the age of 39. Louis Comfort Tiffany’s stance on married women was clear; they could no longer work for him (though, if the relationship failed, they in some cases returned). Louis was a career-driven father of eight children himself, so perhaps his policy derived from his all-demanding style as an employer, as well as his understanding that the relentless needs of children and weight of domestic burdens that fell absolutely on women.

The change in Munson’s life must have been staggering. She married a two-time widower, Frederic F. Sherman, a machine operator in an elevator company, and suddenly became stepmother to his four children—all under nine years of age, including an infant—and inherited two in-laws from his prior marriage. This would have been a change from a life of order and creativity to one of unremitting chaos. A longtime Manhattanite, she moved with her new family out to Yorktown, in Westchester. Outside the structure of Tiffany Studios New York, where her work could shine, at least among her colleagues, Munson’s full talents were neglected. Her husband attracted the patronage of JP Morgan by writing a “sonnet series”—unbelievable as it sounds—praising the magnate’s collection of Folk Art, supposedly winning Morgan’s financial support to found a specialist magazine Art in America.

Munson had always lived modestly, sharing an Amsterdam Avenue apartment with her brother, an electrician. It is therefore impossible not to wonder whether Munson’s accumulated salary from Tiffany Studios New York went to fund Sherman’s sudden career elevation from humble machine operator, not to mention the maintenance of his large, extended family. From the time Sherman transformed himself into a publisher and Folk Art collector, Munson served as his unpaid editor, and is remembered as having never contradicted him or boasted of her prior career, though she had had, it was said, “twenty workmen under her supervision.” Though never prosperous, little recognized, and increasingly impoverished, she was at least named in the “Frederic Fairchild and Julia Munson Sherman Papers 1874,” the couple’s scholarly archive of American art, now housed at Smithsonian Institution.

Munson’s successor at Tiffany Studios New York was Meta Overbeck. Like Munson, she was born in New Jersey and may have begun working for Louis Comfort Tiffany as early as 1903. She was appointed to manage the jewelry department around 1914. Although there are aesthetic and material continuities between the work of two women, the department’s style notably shifted, probably in the late teens. A twentieth century commentator noted that the “missionaries of art” had had limited appeal to the super wealthy, who stubbornly preferred diamonds; Tiffany’s hope that jewels worn by influential clients would be a traveling form of art that elevated taste was all but relinquished. He retired as artistic director in 1918—so, less closely supervised, Overbeck’s designs express a greater interest in contemporary styles and the forms of modernism. As time passed, her jewels increasingly featured large, faceted stones, necessarily placed in heavier mounts, their forms governed more by symmetry and geometry, with a palette defined by bold, definite hues in bright tones. Though more pronounced and bright, color was still the pre-eminent concern. Historicist jewels inspired by Indian and Renaissance forms—and later by Tutankhamun-inspired Egyptian artifacts—appear more often under Overbeck than in the earlier years, as do jade and coral, so important in the Art Deco period.

As time went on, census records reveal that Overbeck described herself as a “designer,” working for a “jeweler,” and this may help explain the stylistic shift evident in the jewelry record. By contrast, her predecessor Julia Munson, deeply engaged with Louis Comfort Tiffany in the early experimental stages of the jewelry effort, told the census takers that she was an “artist.” When Tiffany died and the Tiffany Furnaces closed in 1933, Meta Overbeck left the firm, but remained in Manhattan, living with her mother and then, ultimately, alone. Although less is known of Meta’s later life, this may soon change with a forthcoming publication—she will receive greater recognition for her contributions to Tiffany’s jewelry next month, when Jennifer Thalheimer, curator at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum, publishes Overbeck’s beautiful pencil, ink, and watercolor jewel sketches that were donated by her niece in 1978. The Morse Museum is an important repository of Louis Comfort Tiffany’s work, and the book and accompanying scholarship are eagerly awaited.

Julia Munson and Meta Overbeck were two of several women who helped create jewelry for Louis Comfort Tiffany—there were more. Though the passage of time has obscured aspects of these artists’ contributions, record digitization and the cultural shift toward true equality will advance recognition of women’s important work at Tiffany Studios New York.