French artists like Monet and Gaugin discovered the "emerald coast" of Brittany, Western France, in the 1880s. They captured the independent spirit of the inhabitants, dressed immaculately in their distinctive regional attire, engaged in traditional rural and seaside pursuits such as haymaking, tending animals, fishing, and journeying in groups on foot through the countryside to attend mass. Another activity that captured the artists' imagination was the more unusual activity of the seaweed harvest.

Gaugin and others captured these Breton "Goemoniers'" quiet dignity as they performed this backbreaking work, raking, drying and burning the massive stacks, variously employing horsedrawn carts or the more strenuous hand barrows in their labors. Despite the avant garde nature of the paintings, there was an underlying romanticism to the artists' vision of the Bretons, obedient to the rhythms of the tides and the seasons, yet also imbued with a deep spirituality and devotion, happily remote from urban life. The artists captured them in the many local variations of their distinctive regional dress, all of which represented their deep pride of identity, belonging and representation.

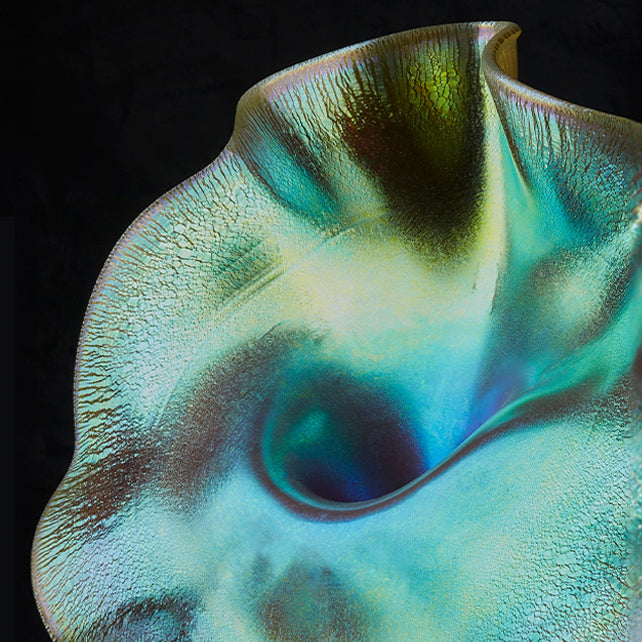

Art Nouveau decorative artists such as Gallé and Lalique were also captured by the Bretons and their isolation from the banalities of modernity and industrialization, their immersion in a slow pace of life governed by nature, in a timeless setting of farmland and the wild Atlantic coast. Gallé famously captured the Breton seascapes in a set of inlaid nesting tables in the 1890s, while his last artwork, crafted in glass in 1904, was "Hand with Seaweed and Shells".

Though there is no surviving evidence the two artists met, they attended many of the same exhibitions of the 1880s and 1890s, while Gallé's study of Darwin and love of Japonismé is believed to have influenced Lalique. Lalique also shared the older Art Nouveau artist's devotion to the observation and representation of flora and fauna, and his desire to innovate. Lalique handled the subject of Brittany and the motif of seaweed in at least two important, documented jewels. One of them, depicting a Breton woman in one of the traditional high coiffes of white lace, as well as sketches of three variations, all dating c. 1900-1902, are pictured in Sigrid Barten's catalogue raisonné of Lalique's jewelry, as #671.1. "The capture of Dejanira" pendant, circa 1900-1902, is a sculptural jewel depicting mythological figures set among a highly three-dimensional, swirling stalk of seaweed (also pictured in Barten, #668). Another early brooch, c. 1898-1900, in the collection of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, a gift of the Marquise Arconati-Visconti, centers a cabochon sapphire among stylized enamel and plique-à-jour enamel seaweed branches. Figural pendants and brooches with pairs of symmetrically juxtaposed figures and animals, including women, peacocks, dragonflies, grasshoppers, butterflies, tigers, wasps, and rams, first appear in the late 1890s, but are frequently seen in the 1903-1907 period.

Through this pendant, Lalique's employs symbols from the sea and political history to express the deep connections of this remote yet once powerful Duchy of Brittany, with its ancient Celtic roots and linguistic heritage, to a vanishing way of life in unity with nature. One of the Breton coats of arms carved into the stone of the 16th century castle at Nantes combines the imagery of royal lions with foliate motifs, including seaweed, and a variation on the motto "Death before Dishonor." The medieval lions reference the ancient claim of the Breton Dukes to the throne of France, and the fact that the Duchy of Brittany remained a sovereign power until the 16th century and beyond, retaining ancient privileges and fiercely resisting full integration into the France of the modern era. The seaweed also references Bretons' ancient ways of life tied to the sea, while the natural pearl symbolizes the riches offered up by it. The sale of the iodine and soda extracted from the seaweed helped Breton families by augmenting their agricultural income, allowing them to maintain their independence and stubborn traditionalism.